Suzanna and I

Transformations in the Representations of History / Mythology and Victimizer / Victim

in the Works of Haim Maor: 1978 – 2008

Artist Michal Na'aman deconstructed the title of one of her works, Scarlet Painting, into "scar let" and "pain ting." By doing so, she revealed the scar and pain hidden beneath its surface. The painting derives from or responds to a wound, an abrasion, or a scar. It is a "pain painting."

In a similar vein, author Amos Oz once said that "every story begins with a wound."

Art that deals with a wound is usually autobiographical. The author or artist "deals" with his or her own biography. His or her artistic journey thematizes a mental, emotional-cognitive burden; in my case, that of a member of the second generation of Holocaust survivors.

The origin of my "pain painting" or the wound from which my story begins is a number: the number 78446. This number was tattooed on the arm of my late father, David Moshkovitz blessed be his soul, upon his arrival in Auschwitz-Birkenau with a 1942 transport of Jews from the town of Płońsk.

In a text published on the occasion of my exhibition "The Forbidden Library" (1994), I referred to the meaning my father's number has had for me. That text was later printed, along with the other texts quoted in this article, in my book Penei HaGeza' uPenei HaZikaron: HaSifria HaAssura (The faces of race and memory: the forbidden library), Tel Yitzhak: Masua, 2005.

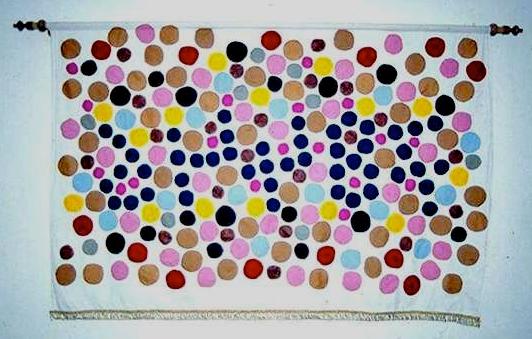

Fig. 1 Untitled (Color Blindness Test), appliqué

"In the beginning there was the number. Blue digits, faded, tattooed in freckled skin, mottled by brown-yellowish stains and graying hair, bowed toward crackled skin, like ears of corn in the wind. As a child, I used to look at the muscular arm of my father and, again and again, recite the numbers: 'seven, eight, four, four, six…' at first in a hesitant whisper, like a personal incantation: 'seven, eight, four, four, six,' and then, uproariously with tempestuous conducting gesticulation […].

A few years later, I was inundated by a linguistic-cabbalist urge.

The dictionary I consulted explained the word tattoo as

'a drawing or symbol etched into the skin,

mainly by puncturing or burning the skin

and spreading into these lacerations an indelible paint.

Tattoos are very popular with some savage tribes, sailors and pilots,

who usually engrave tattoos on their arms or chests.

'Nor [shall Ye] imprint any marks upon you' (Leviticus 19: 28).

But father, certainly, was not a sailor

nor did he grow-up among savage tribes.

'Father, is it true that you didn't want a number at all but were forced to have one?'

Father is silent, his face expressionless.

The wrinkles on his brow and cheeks are like the stripes

on the tattooed face of the Australian aborigine in the dictionary.

I was like a cabbalist or visionary staring at numerals and stars,

trying to penetrate beyond what the eye sees.

I was engaged in deciphering the signs and secrets

of the numerals engraved in the flesh,

as if they were the dates of birth and death on a tombstone,

or a code in a riddle.

I used to play with numbers, like a numerologist,

searching for mysterious meanings.

'Father, are you alive because of the secret combination in blue

that bestowed magical power upon you –

an open account in the checkbook of life?'

In time, I became acquainted with additional numbers:

in the identity card, in a passport, military ID,

telephone numbers at home and at work, bank account number.

But all these numbers did not have the same compulsive,

unnatural attraction, as did the 'seven, eight, four, four, six'

connected with my father's image

like a transparent and impenetrable celluloid wrapping."

Another significant person in this context was my maternal grandfather, Ephrain Rutter blessed be his soul. My grandfather was blinded by the Nazis, and I served him as eyes during all the years of my childhood and youth. The following paragraphs encapsulate my experience of this intimate relationship:

"When I was a child, my grandfather used to tell me

how he cut tombstones in his village in Poland.

There were plain, bare tombstones and there were luxurious marble tombstone

with embossed gilded letters; their heads were adorned with lions and flowers.

He was a renowned master craftsman and much in demand.

At times the noblemen of the area commissioned him

to design stained-glass windows for their mansions and to cut their tombstones.

A Jew amongst gentiles,

my tombstone cutter grandfather was a devout Jew.

And my grandfather told me how peace was disrupted.

Erev Rosh Hashanah (New Year's Eve);

Jews are at prayer and the city square is chilled with anxiety.

Flocks of ravens. Greedy talons and a route cut-off.

My grandfather, steeped in faith,

loses his eyesight at the hand of an armed soldier . . .

Israel. [The town of] Holon is a wilderness and stillness enclosed in white.

An orphaned raven in a cloud. The chill of dawn on the porch.

He brings me books to read, illustrated with wonderful pictures.

'Haim'ke, read the books. Read them to me

and describe what you see in the pictures.'

***

"'A – apple; B – boy; C …'

'Repeat and read again!'

'A – Auschwitz, B – Birkenau, C – concentration camp, etc.'"

***

"Grandpa had a German shepherd female dog. She functioned as his eyes instead of those gouged out at the concentration camp.

Grandpa had another female dog. And there came the cat and ate the kid that father bought for two zuzim. And his two eyes like the kid for a burnt offering."

***

"Grandpa had two handkerchiefs. With one he wiped his nose, and with the other – the secretions from the corners of his blinded eyes.

I spread out the latter one in front of me. Big eyes were opened up in it and pierced my head, Christ's tormented eyes on Veronica's sudarium.

***

The outlines of my face are inscribed in my blind grandfather's palms.

The outlines of my naked and illuminated face retain a thread of longing for one more caress – since he had shed his body and transformed into a ray of light.

***

My blind grandfather taught me that racism is a sickness

of people who see with their eyes.

'When you are blind, your heart opens to all humans, whoever they might be.'

No, I was not raised on hate."

Father's number and the blindness of my grandfather became the main raw materials in my art.

***

"However," Amos Oz continues, "an autobiography is not a confession."

Indeed, an autobiography is not a confession. Borges noted once that it is equally autobiographical whether one writes "I was born in such and such a year, in such and such a place," or "there was a king who had three sons." Whether the artist uses the first person, namely, his or her "personal" voice to present an intimate, familiar-sounding account, or chooses to set his or her narration in more distant and strange-sounding times and places – it is all the same. The only difference lies in the packaging; a more ornate and elaborated packaging might hide the historical truth, but just as well might also expose and enrich the artistic truth, which is supposed to touch the heart of the reader or the viewer.

In other words, just as "the best of a poem is its lie" (Abraham Ibn Ezra), a biographically informed artwork is committed more to its artistic truth than to the factual truth. Artistic manipulations, screens, camouflaging and concealing are the staples of artworks in general, and especially for those of an artist like me. I was raised in a house where talking about the Holocaust was characterized by sophisticated screening, concealing and camouflaging so that "the children wouldn't know or understand" and will grow up in a so-called "sound" Israeli atmosphere. It didn't happen, of course.

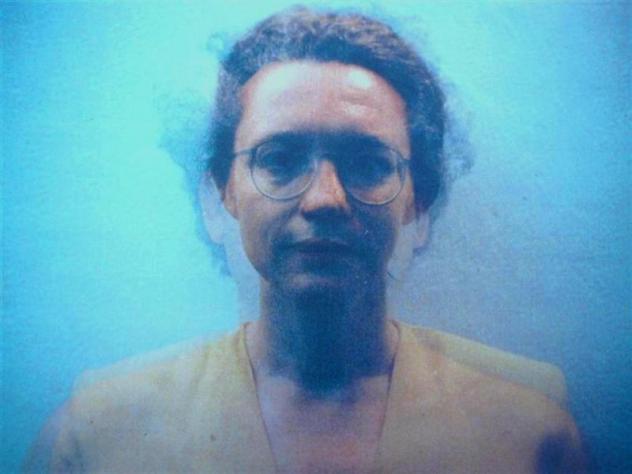

In one of my self-portraits, I am depicted with a big hole in my head – the hole of all that was hidden from me about the Holocaust. Over the years, it has become a "black hole" that has absorbed me.

Fig. 2: Self-Portrait, 1987, Superlac on panel

Self-reflective artistic cognition evolves and unfurls slowly over many years. It is comparable to the unconscious that unfolds like a fan. A paraphrase of a line in a poem by Yona Wallach, the latter sentence implies a contradiction in terms: that which was repressed and stored gradually opens up and surfaces in the consciousness and the work of art; however, like the unfolding fan, it covers and hides the face behind it. The unfolding of one thing therefore also means the concealing of another thing. Openness is but an illusion, a deceit, a mask, an artistic ruse.

In this essay, I'd like to present what I consider the six meaningful conscious-artistic stations that have informed my changing perspectives on Holocaust remembrance and the representations of victim / victimizer, of the Holocaust survivors and perpetrators. Through this itinerary, I will examine my relation with a German woman and with "Germany."

- a. The Mythological Perspective

In my childhood, one used to paint the Holocaust in demonic-mythological terms: the Nazis were portrayed as monsters, the Jews "as sheep to the slaughter," Auschwitz as "another planet," and the Holocaust as apocalyptic eclipse. During the early 1960s, the teaching of the Holocaust in Israeli schools had been problematic, to say the least. It shied from any meaningful discourse of "otherness" and human accountability and from treating the Holocaust as a historical human event. Dehistoricizing the Holocaust had cast it as a sui genri occurrance rather than an event that, given similar reasons, circumstances, mass psychological manipulations, and industrialized genocide, might be perpetrated again in the future (not necessarily by Germans and / or against Jews). Instead, the teaching aimed at demonizing the Holocaust and at instilling the Zionist slogan "From Holocaust to revival." Namely, extermination = Diaspora, and revival = Zionist national self-fulfillment in the Land of Israel.

My artistic creation between the years 1975 and 1983 examined the Holocaust through cultural, archetypal and mythological filters. Parallel Stripes, Circles, The Mark of Cain, Blindness, Metamorphoses of the Sons of Light and the Sons of Darkness, are but a few of the titles I gave to my works or exhibitions that dealt obliquely and in a veiled manner with the Holocaust and the Nazi violence. Current interpretative reading of the material may suggest that my engagement with these themes was nevertheless rather overt and forthright.

The Mark of Cain, the central work in an exhibition of the same name, resembles press photos of alleged criminals with a black rectangular strip covering their eyes to prevent their identification. As far as I am concerned, this is a brutal practice. The media convention of putting black strip on a suspect's eyes, is supposed to protect him but actually renders him helpless, seen but cannot see, blind to the world around him, marked as a "criminal." In the case of "my" Cain, black fabric inscribed with the Hebrew consonant ק (Qof) is covering his eyes and forehead; and this piece of cloth highlights the mark of disgrace and betrays the identity of the photographed person. The design of the letter ק alludes to the Anti-Semite yellow patch worn by persecuted Jews, to Superman's S emblem, and to one bent arm of the Nazi persecutor's swastika. The victimizer, victim and superhero are thus merged into a complex, ambivalent entity presaging my future preoccupation with the dualism of victim / victimizer.

The initial ק on Cain's forehead can stand for his name as well as for various Hebrew words of curse and infamy (קללה; קלון), and clichés that have been hurled at "marked people" throughout the history of different cultures. In English too, the initial C can stand for a plethora of (derogatory) labels: capo, commissar, capitalist, communist, cannibal, colonialist, conformist, cosmopolitan, chauvinist, comic, cunt, clochard, corny, clumsy, careless, crap, crummy, commercial, cursed, etc.

Fig. 3: The Mark of Cain, 1978, mixed media on plywood

b. "Historical-realistic perspective" (1983-86)

April 1983. My first journey to Poland as a member of a delegation of authors and artists, representatives of the State of Israel to the ceremonies marking the 40th anniversary of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. During our stay in Poland: visits to concentration and extermination camps and to remnants of the Jewish culture in Poland. A discovery: the Holocaust was perpetrated by ordinary, cultured human beings against ordinary, cultured human beings, here in Auschwitz on our own planet, Earth. "Gas chamber" was revealed as something like an "Israeli run of the mill bomb shelter," and the "crematorium" is not a furnace of hell, but rather a facility very much like a "bread baking oven." The proportions are human. It is not only "the banality of evil," but evil that disguised its wrong doing behind a banal façade: a father who worked in the camp listened to classical music after work, played with his children and made love with his beloved wife. A work routine! One could even complain about the work load and the foreman's attitude.

In an installation entitled A Message from Auschwitz-Birkenau to Tel Hai, September 1983, I superimposed the silhouette of Tel Hai's courtyard on that of the entrance building to Birkenau. To my surprise, I found out that the silhouettes are quite similar, just as the layout of Homa uMigdal settlements resembles the typical layout of the watchtowers and fences in Nazi death camps.

In the installation, I created a walking itinerary inside the then under construction building of the TelHaiAcademicCollege. Along the itinerary, I planted red directional arrows and green electrical cable. The viewer proceeded from the lit areas to the darker area until finally arriving at an underground shelter where he or she was confronted with the central hybrid image of the exhibition – the silhouette of Tel Hai/Birkenau. Over forty thousand people followed the itinerary I had created without asking themselves where and towards what they were going…

Through the installation, I juxtaposed the Israeli Jew from here and the exilic Jew from there; the fear over there in the gas chamber and the fear over here in a bomb shelter; the Zionist heroic ethos and the heroism of the exilic Jew, which during the Holocaust also included the will tsu iberlebn (to survive). In 1983, this link up between Israeli and Diaspora Jews was tantamount to the breaking of a taboo, at least in Israeli art. The text accompanying the exhibition dealt with this aspect of creating an equation between both systems of heroic ethos.

Fig. 4: A Message from Auschwitz-Birkenau to Tel Hai, 1983, installation

"Walking in Auschwitz-Birkenau and listening to the hidden messages/demons emanating from the fences and watchtowers, the barracks and torture chambers, the gas chambers and crematoria. Listening through the silence and emptiness to the cry and demand, 'Be thine self! Do not deny your feelings! Walk humbly!' And this message is getting stronger and louder: 'Do not deny me, do not deny yourself! Embrace me; hold me tight, I am thine father! Follow my footsteps! Remember, in the gas chamber, I was no less fearless than you are; no more a coward than you are! Walk humbly! Be a peace-loving Jew!'"

Birkenau. The uncannily familiar views: the entrance building that has haunted me since I first saw it in black and white photos. Looking at it, I can confirm that the "real thing" is indeed comparable to the photographed documentation that informed my childhood. Ravens circle around the fences. A text I wrote in one of my works from the "Blindness" exhibition resurfaces in my mind:

"A raven turneth aside to tarry for the night. / A tilted moon lurks / over a van Goghian field of fearful obstacles. / Blind host makes its way / into a path nipped in its prime / into a path slain in its heart."

Here are the ravens, here are the fields, here is the path-railway, but where is the lamb for the burnt offering?

Upon leaving Birkenau, I ask the driver to stop some five hundred meters away from the camp. The car stops. I get out of it holding two cameras. In a swift movement, I direct them towards the entrance gate of Birkenau and "shoot," with bated breath, six pictures, one after the other.

c. "The Confronting Perspective" (1988)

April 1986. First face-to-face encounter with a German; or, more precisely, a German woman, Suzanna, granddaughter of active Nazis – one a Wehrmacht officer, the other a physician who had been involved in the killing of mentally and physically handicapped people within the framework of the Nazi "euthanasia" program. The encounter had shaken both of us but also led to work and friendship relations, which have lasted for 14 years and brought forth several installations.

The first installation was preceded by a number of works that dealt with my father's number with relation to color blindness tests. It was here that I also first started to deal consciously with intergenerational transmission of Holocaust traumata among children of both Holocaust survivors and perpetrators. The number appeared as a key image the relative position of which in the painting produced various meanings. The disintegrated and distorted portraits allude to a "heart-quake," for example in the work Disturbed Head.

The sources and raw materials were drawn, among other things, from Nazi pseudo-scientific racial literature and the photos I had taken during my first visit to Germany in 1987.

I met Suzanna during her stay in Israel as a kibbutz volunteer. The learned and sensitive young German woman, who spoke basic Hebrew and was well versed in Jewish history, managed to thaw my frosty relation with Germans and virtually became part of my family. As a matter of fact, she was for me the first "short-term" German. I remember my many revealing and painful conversations with her, conversions in which I asked her the hardest and most burdensome questions concerning the Holocaust and its implications on us. She "valiantly" withstood my onslaughts and answered my questions truthfully (or, at least, so I believed). Sometimes, she indicated that she felt uncomfortable with some of the traits identified or known as "German mentality," which were also inscribed in her (by nature or nurture?).

Some time after her return to her parents' home in June 1986, I began working on my exhibition "The Faces of Racism and Memory." Having heard that I had arrived in Germany to collect materials for the exhibition, she vehemently insisted on serving me as a guide, an interpreter, or a companion, as I saw fit. I accepted her offer. Actually, I was quite happy to share with her the experience of the present in the light or shade of a past that was relevant to both of us, albeit in different ways.

Later on, in Suzanna's room, I asked to see her family albums. Suzanna went to the next room and returned carrying a dusty box filled with faded photographs arranged in brown envelopes. "These are photos of my grandparents," she said.

I looked at the photos and sheepishly joked about their resemblance to "Jewish faces." One photo froze my blood: a handsome man in an officer's uniform. "This is my paternal grandfather," Suzanna said, "No, he wasn't a Nazi. It is the uniform of a signal corps Wehrmacht officer. No, no one in my family was a Nazi. I've checked it out. They were ordinary folk. They knew nothing…"

I picked up the photograph and brought it close to my eyes. The black speckle on the man's chest seemed like a swastika. I put the picture back in its place and closed the box.

Upon returning home, I immersed myself in intense work toward the exhibition that was beginning to take form in my mind. It was clear to me that portraits – of my family members and friends, of Suzanna's family and of other people – were to be the central axis around and through which the audience would move along; portraits that would be displayed as a genealogical tree: from two portraits (Suzanna and I) to four/five (both of us, my parents and dad's number). Next, on two opposite white walls would hang two 30-strong groups of faded black-and-white portraits – 30 of women and 30 of men – facing each other, like the photos of inmates I had seen at Auschwitz-Birkenau's "death block."

However, in my case, the portraits were to be of (Israeli Jewish and German Christian) family members living today. In the third station, I would paint all the characters on cracked wooden panels, like icons or, mainly, like the death masks from Faiyum I had seen at a museum in Berlin. At the end of the tour, the viewer would enter a very small room, sit on a chair and examine the multiple reflections of his or her image in three crystal mirrors. It would be a "sound box" in which the present and the past would resonate and mutually hone each other; in which the viewer and the viewed, the victim and the victimizer, would emanate from the same source and would be projected onto the same mirrors. And in which there would be no "other."

From here, from the end of the tour, the viewer would retrace his or her steps, reexamine him- or herself, reassemble things forgotten and fuse the "wound" with the "tikkun" (healing).

1988. My "Faces of Race and Memory" exhibition at the Israel Museum, Jerusalem – a confrontation of my family, Holocaust survivors, with Suzanna's family, perpetrators of the Holocaust. Both families appear as "willy-nilly actors/players" in a play or a simulation game that transforms the present into the past and in which the past is reflected in the present. The exhibition is constructed as an experiential tour of the viewers who, in their turn, become participants in the play-game. The four-station tour begins with passive watching and ends with active contemplation: prologue, face of the race, face of the memory, a sound box.

Fig. 5: Disturbed Head, Superlac on wood

d. "The Perspective of Mythology vs. History" (1994)

My heart to heart talks with Suzanna and the work on the installation as well as people's reactions to seeing it made me understand that the perspective that contrasts mythology with history interests me and merits further investigation. The results thereof can be seen in two installations which were exhibited simultaneously in two historically and emotionally laden sites: Tel Hai and the Givat Haviva Yad Ya'ari Archive. In both of them, the heroism and commemoration of historical-cultural heroes overshadow and even erase those of other participants who had no "cultural agents" or "chroniclers" to tell their story.

In the installation Ohel Shem (literally: tent of Shem or tent of a name), it was the figure of Joseph Trumpeldor alongside seven people who were "erased" from historical memory.

In the installation Reik against the Reich, it was the figure of Haviva Reik and other Eretz-Israeli parachutists, whose memory was almost erased in the shade of the most prominent parachutist of that group – Hannah Senesh (author of the poem "A Walk to Caesarea").

Fig. 6: Reik against the Reich, 1994, in stallation

e. "The Complementary Perspective" (1994-2000)

1994. The Forbidden Library installation contrasts my biography with that of Suzanna.

1996. In the installation Suzanna Shoshana, Suzanna assumes a double identity, that of a Christian German woman and that of a Jewish Israeli woman and is revealed as Anima, the artist's female alter ego. One of the installation's works associates the victim with the victimizer in a symbiotic union.

2000. The installation Anima, Animus, Anonymus confronts two women: Suzanna, a Christian, German, European woman, a romantic female figure, cold and unattainable, a sort of a princess from Grimm's Fairy Tales; and Rachel, an oriental Jewish, Israeli woman, a warm terrestrial woman, the epitome of mother earth, with a touch of orientalist eroticism and Gauguinesque references. This was the last installation in which Suzanna participated. After 14 years of friendship and collaboration, she decided she didn't want anything to with me anymore. The formal reason she gave me had to do with the events of the second Intifada. Other reasons remain a matter of speculation.

Fig. 7: Suzanna and I, Double Exposure, 1994, color photo

f. "The Reflective and Trusting Perspective" (1995-2007)

From 1995 to this day, I have been a member of a TRT group presided by Prof. Dan Bar-On, a social psychologist at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev. In an article Bar-On contributed to my aforementioned book, he described the beginning of our relationship and my joining his group:

"I got acquainted with Haim Maor's works in a special way. […] In the mid-1980s, I went to see his exhibition 'Faces of Race and Memory' at the IsraelMuseum in Jerusalem. I didn't know anything either about him or his work. I walked into a room and was asked to […] determine whether the pictures on its walls were portraits of Aryans or Jews. Something inside me rebelled: 'It's a Nazi idea. There isn't such a thing; one cannot recognize races by looking at faces!' But as I walked along the room, looking at the faces staring at me from the walls, I started realizing that I too had my own system of classification – some faces seemed to me somewhat 'Jewish,' whereas others (Suzanna's, for example) impressed me as veritably 'Aryan.' I had to admit to myself that indeed these stereotypes are also embedded in me. Going further and further, the painted faces were increasingly 'losing' some of their features: is it possible to recognize 'Jewish' or 'Aryan' faces solely based on the shape of their noses, or hair color? Towards the end, […] I was asked to enter a dark room equipped with a chair and a mirror. I sat down and looking at my reflection, asked myself: do I look Jewish? Do I look Aryan? Out in the busy Jerusalem street, I looked at the people around me and mumbled to myself: Jewish or Aryan? I was fascinated by Haim Maor’s profound psychological insight and amazed at the extremely elegant manner in which he succeeded in evoking in me the human biases I share with the rest of humanity."

TRT, the name of Prof. Bar-On's group, is an acronym of "to reflect and trust." It is a dialogue forum between American and Israeli descendants of Holocaust survivors and descendants of Nazi perpetrators.

The group's activity led to the involvement of some TRT participants in the moderation process of working through current ethnic conflicts (between Catholics and Protestants in Northern Ireland; Blacks and Whites in South Africa; Palestinian and Israelis). It was always a joint-moderation pairing up descendants of Holocaust survivors and perpetrators. I found out that the perquisite for mutual understanding and respect and even peace making is a dialogue and consciousness transformation. These, in turn, are constructed by individuals willing to listen to the story of their "other" and to recount their own story. Contrary to the "grand narrative of the victor," or "History," it is "his-story" and "my-story."

From among the many amazing and meaningful moments I had experienced in these encounters, I'd like to mention two symbolic ones:

One such moment: I asked an Irish terrorist with "blood on his hands" why he did what he did. His answer was: “Because of the responsibility. You know, responsibility is the ability to respond.”

(In parenthesis, I'd like to point out that etymologically the English word "responsibility" derives from the Latin "responsum" – "something offered in return." Thus it denotes reciprocity as well as accountability, or answerability.

The Arabic noun مسؤولية [pronounced: mas'uliyya] is derived from the root verb سَأَلَ [pronounced: sa'ala] – "request an answer."

The Hebrew word אַחֲריוּת [pronounced: akhariut] derives from the preposition אַחַר [pronounced: akhar] – after, or behind as in "standing behind someone or something." In unpointed Hebrew, the word also contains the adjective אַחֵר [pronounced: akher] – "other." It can be argued, in the spirit of Emmanuel Lévinas, that only if you are able to contain within you your "other" and be responsible for him or her you actually abide by the command "love thy neighbor as thyself." Yet love cannot be commanded, only mutual respect. Therefore you should, at least, respect your neighbor as yourself and thus win his or her respect.)

The other moment: Having listened to the stories of second-generation Holocaust survivors, Fatma, resident of a refugee camp in Gaza, remarks out loud that she is sick of listening to Holocaust stories. She says that she was taught that the Holocaust never happened and these stories are nothing but a bunch of Zionist propaganda lies. Her comment almost breaks up the meeting. After a few minutes of turmoil, a member of TRT, Martin Bormann Jr., son of Hitler's private secretary, seats himself next to her, silently takes her hand, and says: "I'll tell you what my father did in World War II." For twenty minutes, he describes to her and to the other participants the process of extermination of the Jews from his point of view.

When he finishes talking, Prof. Dan Bar-On leaves the room agitated and tells me that all his years of research were made worthwhile by this surrealist moment in which the German Martin Bormann Jr. told Fatma, the Palestinian, what the Nazis had done to the Jews. For me, in this moment art stood still in front of reality, saluted it and said: "each wound is born of a story."

As time went on, my outlook on victim / victimizer relationship has changed. I came to understand the complexity of this relationship and its psychological aspects, as can be demonstrated by the following stories from other TRT encounters.

A South African black man, former senior member of the resistance movement against apartheid, told me that he wasn't interested in wasting his mental energy on hating his white tormentors. He said that he'd rather live and love life, while his tormentors wallow alone in the cesspool of their deeds. The punishment of the victimizer, he argued, is to remember the eyes of his victim.

Martin Bormann Jr., a priest who also worked in Africa for a while, was once summoned to the bed of a dying man. Unfamiliar with the biography of his confessor, the man told him from his deathbed that he was among the soldiers who had crushed the Warsaw ghetto uprising. On order of his commander, he shot a Jewish girl who walked towards him with her hands raised up. Her big astonished and frightened eyes were etched in his mind. Every night, for years, they came back to haunt his dreams. "Set me free of these eyes," he asked the priest beside him, without knowing that he was the son of Hitler's private secretary…

The strong personal relationships that were forged in the TRT encounters between people with common interest in art or other fields continued also outside its perimeters. Thus, for example, in 2007 I took a picture of myself and a fellow TRT member, Dirk Kuhl, on the balcony at the Nuremberg stadium. Kuhl is the son of a concentration camp commander sentenced to death at the Nuremberg Trials, and for us our joint photo was a token victory over our weighty historical-familial burden.

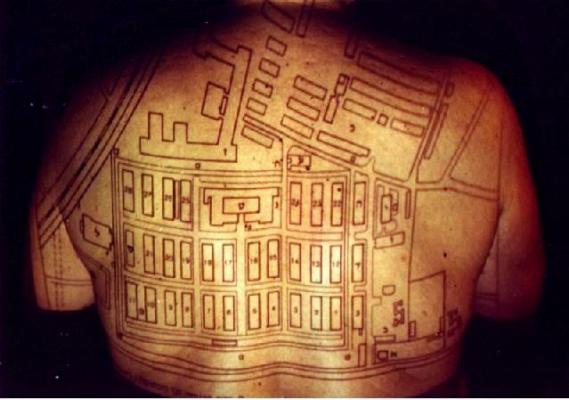

Fig. 8: Untitled (Map of Auschwitz), 2001, color photograph

In my current works, I present an anonymous human body carrying on its back, knowingly or unknowingly, a sort of a tattoo of the maps of either Auschwitz or Birkenau. Who carries this weight? Is it a Jew or an Israeli? Is it an Aryan or a new German? The German mania still runs in my veins, searching new vents or outlets for expression.